Lowest to Highest Route Death Valley

Badwater Basin, CA, USA

Mt. Whitney, CA, USA

With temperatures that can reach 130 °F (54 °C) Death Valley is the hottest and driest of the national parks in the United States. The...

Al Arnold’s 146-mile trek from Badwater, 282 feet (86m) below sea level and the lowest point in North America, to Mt. Whitney, California, USA, took place in 1977 after two previous attempts. The 2 places are only 84.6 miles (136.2 km) apart, but the course’s cumulative elevation gain exceeds 19,000 feet (5,800 m).

The route had been hiked in 1969 by Stan Rodefer and Jim Burnworth.

In 1970, Kenneth Crutchlow (1944-2016), originally from England, had raced Bruce Maxwell (1948-1998), a tennis professional, across Death Valley (lengthwise) for five days.

In August 1973, Kenneth Crutchlow and Paxton “Pax” Beale (1929-2016), from San Francisco, ran a two-man relay from Badwater to the top of Mt. Whitney.

In September 1974, Bruce Maxwell and Tate Miller (1948-), both from Santa Cruz, California wanted to also attempt the two-man relay, by alternating every three miles and broke the previous record in 33 hours, 15 minutes better than Crutchlow and Beale.

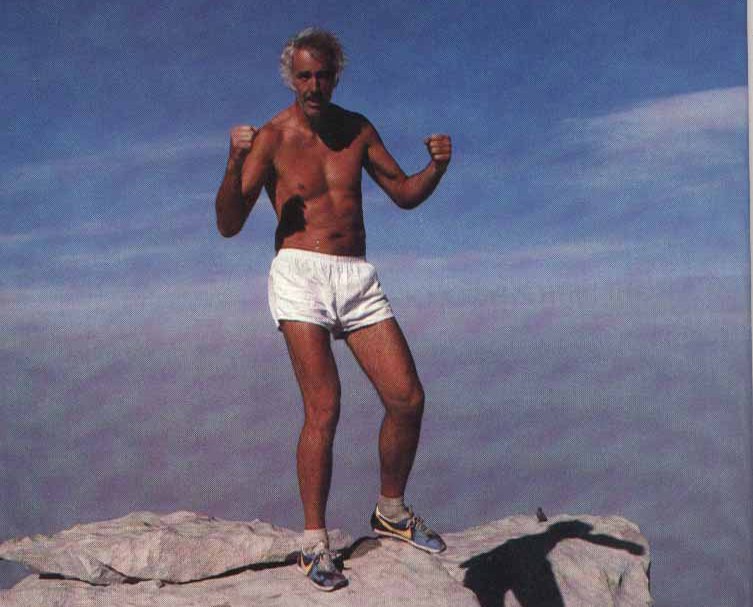

Al Arnold was the first to run the 146-mile from Badwater Basin to Mt. Whitney solo, self-supported.

During his first attempt in 1974, the 49-year old Al from Walnut Creek, California, was pulled off the course after eighteen miles (29 km) with severe dehydration. Although he had done lots of heat training, his longest run had been only 4 hours.

After more long distance running he attempted again in 1975. The weather conditions were the best he could wish for, but a knee injury aborted the run at fifty miles. In Al Arnold’s own words:

“Twice I failed! In 1974 I almost killed my running partner, Dave Gabor. He collapsed at Furnace Creek. I continued on to ‘The Oasis’ when I stopped. I couldn’t stop worrying about his safety. I lost my focus. It was over. It took him a year to recover. By the way, the temperature at Stovepipe Wells was 121 F – AT MIDNIGHT! The mid-70’s were drought years. Just perfect to challenge the desert at its worst. Yes, I’m still alive:) David’s collapse was because of an intolerance to heat. I failed because I couldn’t stay focused. My second attempt was in 1975. Everything was fine until Towne Pass, at which point my left knee would not support downhill running. On my way to Stovepipe Wells I had gotten cute and tried running across Devil’s Golf Course. The crust couldn’t support my 225 pounds and so I hyper-extended my left knee. Again, I lost focus.”

In 1977, after 12,000 miles of training Al knew that, no matter what, he would not give in. This time his solo effort had to succeed: it was just him and his support crew against the elements and the clock.

After many days of running in solitude, vigorous sauna-training and desert acclimatization, he was mentally and physically strong. But the most important part was detraining himself to go slow enough to be able to bear the heat. He knew this would be his final attempt. He was confident he would succeed this time.

It wasn’t about the speed, it was about completing the ‘damn thing’, while enjoying and sharing what he was doing with people he’d meet along the way.

“Without the crew, there can be no runner.”

Al Arnold

On August 3, 1977, he started at 5AM in Badwater and jogged, walked, climbed the 146 miles to the top of 14,496 foot Mount Whitney, which caps the Sierra Nevada on the western border of Death Valley.

“I was excited about the beauty and fantasizing about the old prospectors, the Indians, the battles that might have been fought… the people out here struggling or perishing maybe within a few feet of where I was running.

Yet I was fully prepared, fully confident, eager, glad to be on my way and thrilled by the enormity of what I was trying to conquer,” Al said.

“I had to do it with humility. If I tried to attack, I’d fail. To run eight-minute miles was attacking, to run them in nine was still attacking… I had to drop down to 15 even 20 minutes for a mile. That takes a whole different motor response in the muscles. You don’t have the momentum going for you.

It’s a matter of conserving energy, keeping the pulse rate low and preserving your fluids. It’s as if you were making a lemon meringue pie; fold it too fast and you destroy it. That was my analogy: I was folding myself through the desert.”

“The worst part of the run was the first 15 hours. The enormity of the heat gets compounded by the fact your adrenaline is up; the two elements combined could have been devastating.

But then on the second day I relaxed… maybe I should have begun to run a day earlier.”

After covering 40 miles in 10 hours Al got sick and his knee really hurt.

His two-man support team, Erick Rahkonen, a newspaper photographer, and Glenn Phillips, a commercial pilot, were also sick after a long day driving slowly through the boiling heat. But they kept pushing through.

Al had to climb over the Inyo mountains before descending into the searing Owens Valley where violent winds blasted him with sand and silt.

“That was the first time I could see Mount Whitney and I said to her ’Well, you probably thought you’d never see me but I’m going to be on top of you.’ She’s a very powerful lady and I didn’t want to conquer her; just be part of a relationship.”

After 3,5 days of struggle, Al reached the top.

He just stood up there and looked back to where he’d started and he couldn’t believe he’d done it.

“You couldn’t even begin to see where I’d started. There was a valley, then a mountain, a valley and a mountain, disappearing 146 miles into the haze. It had taken me 84 hours. Maybe someday I’ll go back there and realize what I’ve done.”

Al never returned to the course, except when he received the Badwater Hall of Fame Award.

It took four years before Al’s record was broken by Jay Birmingham in 1981, in 75 hrs, 34 minutes.

In 1987, the crossing became an official, organized footrace and now it’s an annual, invitation-only event called Badwater 135. The first year only five runners took part.

Al didn’t consider himself to be a natural athlete, but he always stayed in good shape and enjoyed running. Throughout his life he managed two athletic clubs and coached numerous local professional athletes.

Al Arnold passed away peacefully on September 6, 2017, at age 89.